India’s manufacturing journey has been a reflection of its growth, shortfalls, and transformation. While it started off at a similar economic level to China in the early 1980s, India’s manufacturing GDP has hovered around 15 to 16% for several decades. The Make in India initiative in 2014 brought about the change that had been long overdue. With the support of a chain of reforms aimed at making business easier, upgrading infrastructure, and fostering domestic production, the sector has grown to account for almost 17% of GDP. Nevertheless, raising the national target of making the manufacturing sector account for 25% of GDP is still a long shot and calls for more radical change.

The global landscape for trade is adding a layer of complexity to the issue. The waning of multilateral agreements and the increasing reliance on bilateral and free trade agreement-based negotiations are profoundly changing the nature of global trade. Changes in policies like reciprocal tariffs introduced by the United States have made the future uncertain for sectors that rely heavily on exports. Though the current effect on India’s exports is limited, these changes signal the need for India to work towards becoming an “Atmanirbhar Bharat” by building up the country’s domestic manufacturing capacity. A strong manufacturing base is not just a driver of domestic growth towards Vikshit Bharat @2047, but also a buffer against external shocks and a pillar of long-term economic security.

For the dream of a Viksit Bharat to come true, India has to scale up its economy from 4 trillion dollars to almost 20 trillion dollars. It will have to increase per capita income fourfold, create real jobs for millions, and ensure that progress aligns with commitments to the environment, including the national goal of reaching net zero by 2070. The manufacturing sector will become the core of this metamorphosis, serving both as a multiplier for services and as an absorber of the surplus labour force.

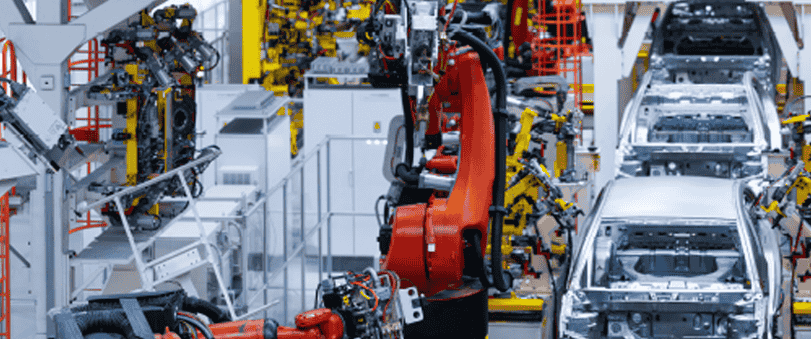

Within manufacturing, India exhibits varying levels of global competitiveness across 10 to 11 value chains. On one hand, the country has built competitive advantages in skill-intensive sectors like automotive and capital goods. On the other, it still lags behind in raw-material-intensive sectors such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and textiles. India’s involvement in technology-intensive industries such as electronics, semiconductors, aerospace, and renewable energy remains limited. However, recent significant investments by both international and local companies signal that India is setting the stage for a strategic upward shift in these sectors of the future.

India is blessed with three structural strengths which, if leveraged properly, can serve as powerful engines of this transformation. The first is its broadly based manufacturing sector, positioned to benefit from shifts in global value chains. The second is its demographic dividend, with nearly 30% of the population being young and entering the labour market at a time when many developed countries face ageing populations. The third is India’s robust digital ecosystem, which provides a natural interface between technology and industrial production.

Still, a major issue remains unaddressed. Indian youth are not adequately prepared for the needs of advanced manufacturing. A key reason for this gap is that traditional engineering curricula lack the capabilities required for automation, understanding Industry 4.0 tools, and addressing the rising importance of sustainability. Most students lack exposure to applied technologies, real-world manufacturing environments, and the business decision-making frameworks necessary for industry roles.

Therefore, India needs a global workforce development model that combines the best practices of the world with a locally scalable strategy. Much can be learned from Germany’s practice-based system, Japan’s process-focused training culture, South Korea’s industry-academia collaboration ecosystem, and China’s large-scale skilling initiatives. Giving higher weight to experiential learning, advanced manufacturing technologies, and deeper industry involvement in curriculum design will be essential.

The National Education Policy (NEP) is a strategic instrument to reorganize the education system. By endorsing multidisciplinary learning, integrating vocational education, and strengthening collaborations between academia and industry, NEP sets the stage for training personnel who can meet the demands of future manufacturing and technology sectors. The flexibility, applied learning, and skill development required for transforming the MET sector are aligned with the policy and support India’s aspiration to create a globally competitive talent pool.

Educational institutions need to adapt curricula so that students can function effectively in international industrial settings after graduation. Achieving harmony between academic instruction and industry needs will be essential. This will require the use of digital learning tools, data-driven methods for programme refinement, and the promotion of innovative thinking. India must also strive to make manufacturing intellectually engaging and aspirational. Initiatives such as Atal Tinkering Labs are influential in sparking early interest, but sustained efforts are required at all levels of learning.

As India advances its manufacturing agenda, the need to communicate the opportunities the sector offers is increasing. Manufacturing today is not merely associated with manual labour. It is a blend of engineering, data, automation, and strategic decision-making. This is best described by the MET sector, which stands for Manufacturing, Engineering, and Technology. The move towards digital factories, robotics, AI, and sustainable production models is shaping industrial careers of the future.

In this new scenario, India requires a fresh pool of professionals: Techno-Managers. These individuals have strong technical foundations along with managerial skills. They can interpret technology trends, optimise operations, manage teams, take risks, and contribute to business outcomes. Institutes such as NAMTECH are attempting to bridge the traditional gap between engineering an d management by developing industry-ready professionals through applied learning and industry immersion, transforming manufacturing enterprises into agile, innovation-driven organisations.

India’s future manufacturing leadership will depend significantly on Techno-Managers. Their ability to combine technical knowledge with strategic thinking will define the country’s capacity to scale, compete, and adapt to global changes. India’s ambition to become an industrial powerhouse will require substantial investment, but nurturing this talent pool will undoubtedly be one of the most important priorities.

Designation :

26 December, 2025