Over the past few months, two significant events, the India Semicon 2025 & Vibrant Gujarat Regional Summit placed a sharp spotlight on one central theme: workforce development for advanced manufacturing. Both forums converged on one crucial question how we’re actually training people for advanced manufacturing, and whether our current approach is working?

The discussion covered topics such as skilling frameworks, differentiated practices, and evolution of training models. After spending significant time in this space, however, I’ve learned that the real story is much simpler. It’s about the gap between what we teach and what industry actually needs. And more importantly, how a few institutions are finally figuring out how to bridge that gap.

The Framework Confusion

Let me start with something encouraging we’re surrounded by frameworks.

Europe has the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), Australia has the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF), and here in India we have the National Skills Qualification Framework (NSQF). Each one is thoughtfully built, and on paper, they all make a lot of sense.

The philosophy is good: move away from rote learning, focus on learning outcomes, define what people should actually know, understand, and be able to do. Competency-based education, right? That’s the promise.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Take our NSQF with its 10 levels. At the lower levels, say, levels 1 through 4, it genuinely works as intended. You’re training technicians and operators. The focus is on doing: Can you operate this CNC machine? Can you maintain this robot? Can you run an automation line without shutting down production?

But as you climb to levels 8, 9, or 10, which correspond to Bachelor’s, Master’s, and PhD programs, the nature of competencies naturally evolves. Here the emphasis shifts more toward knowing, analysing, and researching, which makes sense given the academic nature of these qualifications. It’s an interesting design choice that reflects how we think about higher education, bridging practical competencies with theoretical depth and research capabilities.

The Sectoral Framework Layer

Beyond these national frameworks, there’s another important dimension, the sector-specific frameworks driven by sector skill councils. In manufacturing, the Capital Goods SSC and Electronics SSC collaborate with industries to define skill requirements for robotics, mechatronics, process automation—essentially mapping what’s actually needed on factory floors.

This sectoral approach captures industry nuances well in theory. But in practice, it faces real constraints: limited training scope (sometimes just short courses), weak pedagogy with insufficient hands-on learning, infrastructure challenges at training centres, and curriculum that can’t keep pace with rapidly evolving technologies.

That brings me to what I find most promising: the industry-academia integrated models. These aren’t frameworks in the policy sense—they’re more like practical arrangements where universities and industries stop talking past each other and start building something together. Joint curricula design, shared labs, co-assessment. Real partnerships.

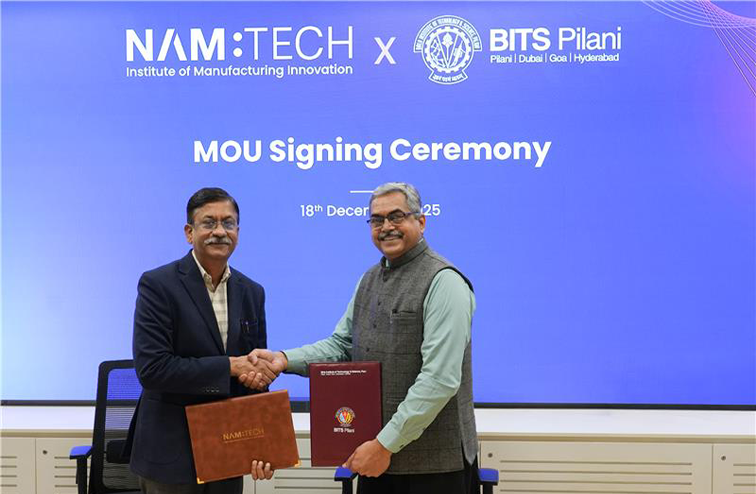

Places like NAMTECH are doing this well, and I think this is where the future lies.

Ways In Which ‘The NAMTECH Approach’ Is Different?

I see four ways how NAMTECH’s techno-managerial Master programmes for high-growth industries are different from traditional academic programmes:

- Starting with the job, not the syllabus

Traditional academia starts with a syllabus – a list of subjects to cover. The newer approach starts with an occupation. What does a mechatronics technician actually do every day? What problems do they solve? Then you reverse-engineer the curriculum from there. Each module is built around a skills map, designed with industry partners, aligned to international standards. It’s a learning journey, not a collection of isolated theory courses.

- Learning by doing, not just listening

The delivery model has changed completely. Instead of lecture halls, you have labs. Instead of theoretical problems, you have live projects. At NAMTECH, 60-70% of contact hours are hands-on—simulations, equipment operation, real troubleshooting scenarios. Industry experts co-teach alongside faculty, bringing actual case data from their plants, talking about process deviations they dealt with last week. The equipment isn’t locked in university storerooms—it’s shared with industry and constantly in use.

- Proving you can do it, not just explain it

Assessment is where this really matters. Traditional universities test what you know. Can you explain how a PLC works? Fine, you pass. But these integrated models test what you can demonstrate. Can you actually program this PLC? Can you diagnose this fault? Can you debug this control system under pressure? Practical learning helps students apply what they have learned in their respective jobs.

- Evolving toward co-ownership

I see this happening in three phases. First, industry and academia collaborate on occasional projects. Then they start co-designing programs. Eventually, and this is where we’re heading, they co-own the entire process. I think the next evolution is “learning factories” where production facilities double as continuous learning spaces. You don’t leave the ecosystem to upskill—you’re always learning while working.

What Needs to Happen Next

Looking ahead, I’m convinced we need to embrace modular, lifelong learning. Technologies in advanced manufacturing evolve too fast for one-time training. The days of learning something once and coasting on that knowledge for 30 years are over—if they ever existed.

We need stackable micro-credentials. Learn automation basics. Add smart manufacturing. Then AI-driven predictive maintenance. Each step builds on the last, and you can do it without leaving your job. That’s the model that will work.

Institutions like NAMTECH are already moving this direction, and I hope others follow.

Final Reflections

Advanced manufacturing doesn’t just need skilled people. It needs people whose skills keep evolving. The frameworks and models we build today will determine whether our workforce is adaptable, employable, and innovative tomorrow.

Here’s what keeps me optimistic: Indian youth are ready. They’re capable. They’re eager. They’re often just one good training program away from being world-class.

If we get this right—if we align our frameworks, break down the walls between industry and academia, and commit to continuous learning—we can do something remarkable. We can make India not just the factory of the world, but the skills capital of the world.

That’s the vision. Now we just need to build it.

Designation : Associate Professor

16 December, 2025